Brilliant Paintings

2012/13

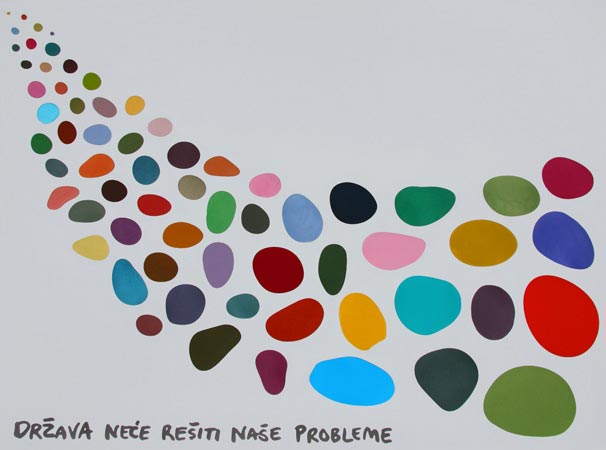

The State Will Not Sove Our Problems, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 92x124cm

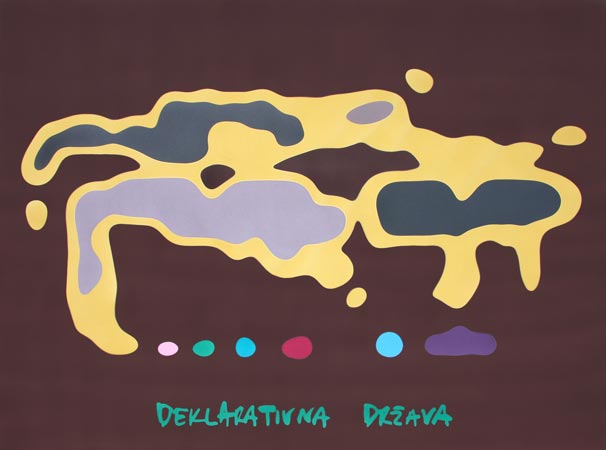

Declarative State, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 92x124cm

Inherited Ignorance of Communication, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 92x124cm

Islands of Interested, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 92x124cm

Power Without Obligation, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 124x92cm

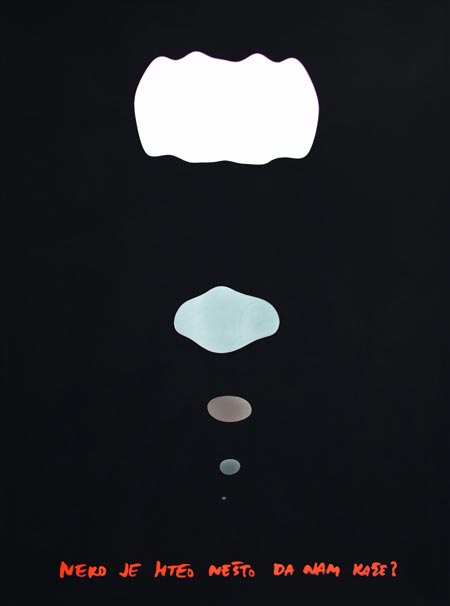

Did Anybody Want to Tell Us Something?, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 124x92cm

Overrun of Mentality, 2012, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

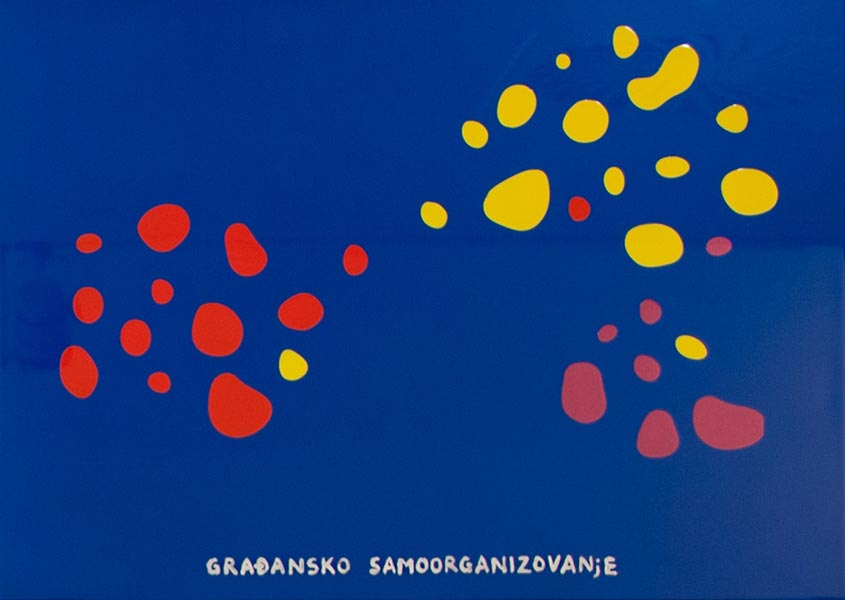

Civic Self-organization, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

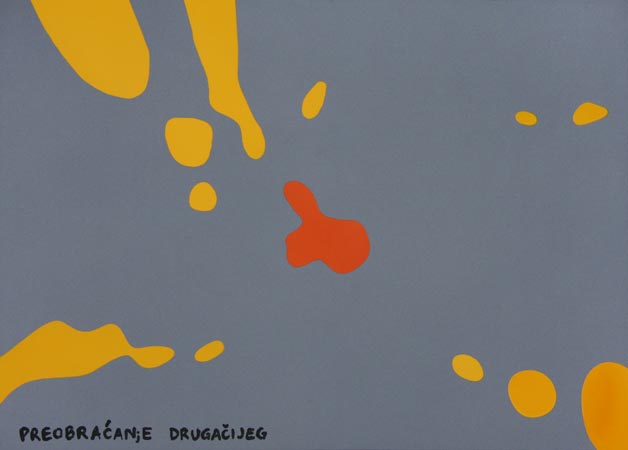

Transformation of the Different, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

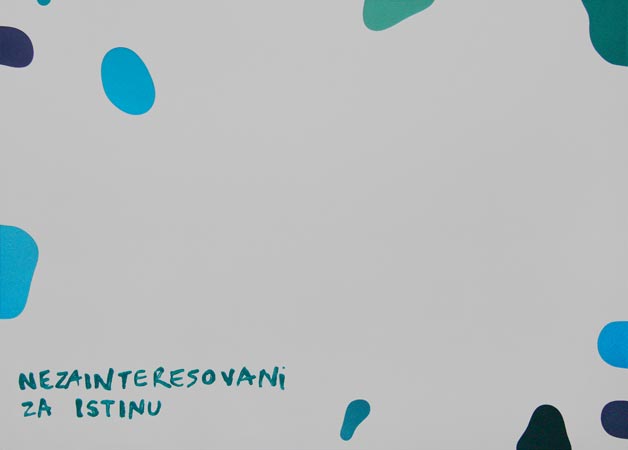

Indifferent to Truth, 2012, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

Order is Treatening, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

Patriotism of Public Funds, 2012, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

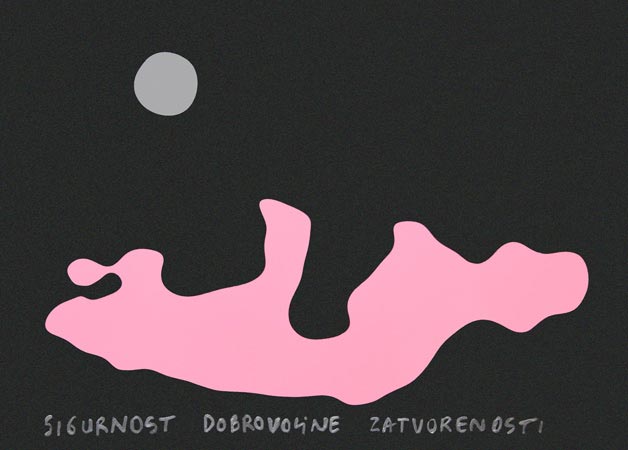

Certainty of Voluntary Isolation, 2012, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

Anonymous and Interchangeable, 2012, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

Freedom Larger-than-Permitted, 2012, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

Vortex of One Truth, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 46x64cm

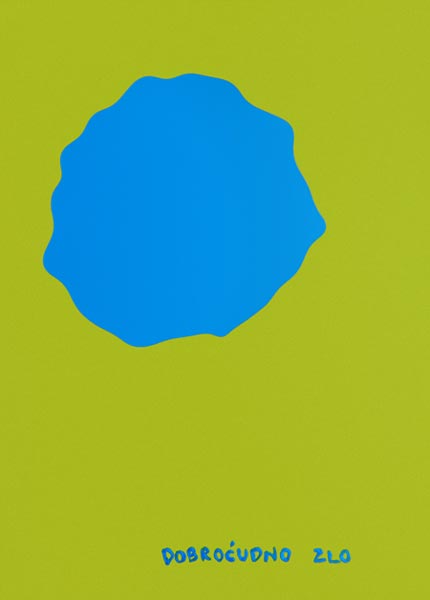

Benign Evil, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 64x46cm

C’mon, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

I Will, 2012, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

Thank You, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

I’m Sorry, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

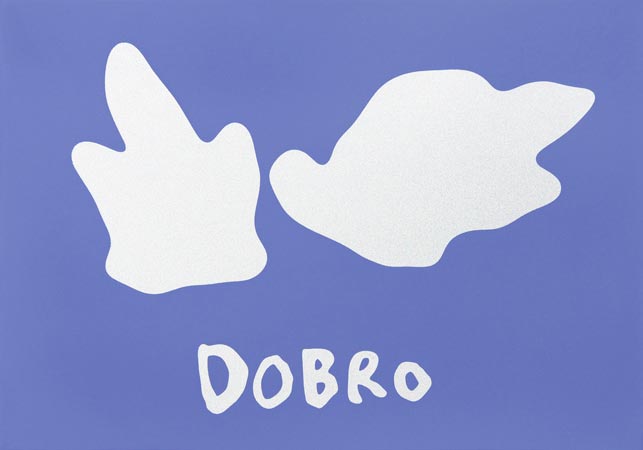

Allright, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

Please, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

OK, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

Yes!, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

Talk to Me, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

I’m Listening, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

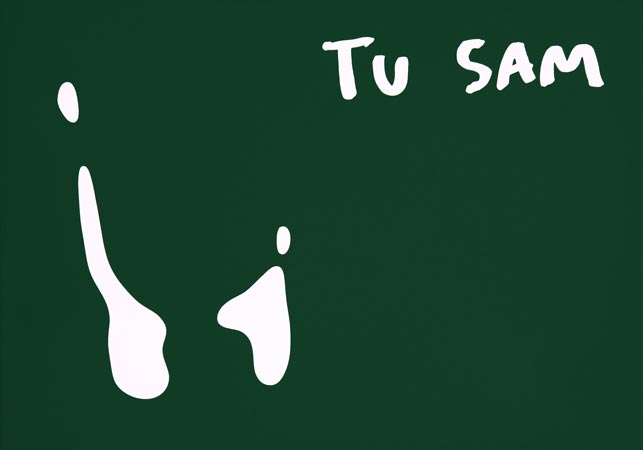

I’m Here, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

It’s OK, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

I Love, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

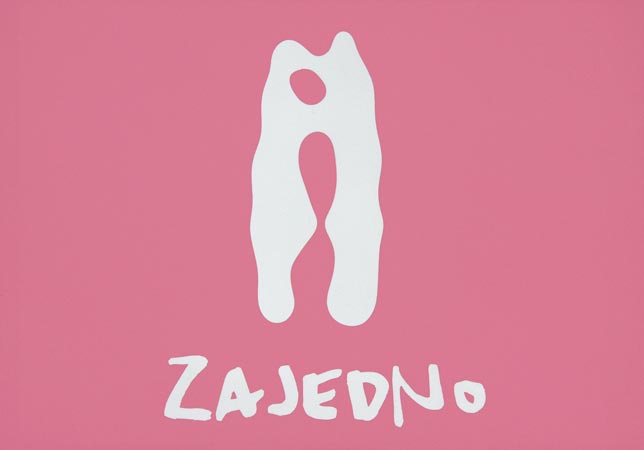

Together, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

Hallo, 2013, metallic paint on aluminium, 21x30cm

[vc_row css_animation=”” row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Ana Bogdanovic

Can Paintings Solve Our Problems?

Zolt Kovac’s Brilliant Pictures are publicly displayed for the first time in the year celebrated as the hundredth anniversary of very important, even decisive artistic projects in the history of modern art. Since 1913. the institution of modern art has been gradually emerging and gaining acceptance in the public and popular discourse of Western European and American culture.(1) Abstract painting as the final outcome of self-sufficient modern painting, received in 1913 significant elaborations in the works of Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, Robert Delaunay and Ferdinand Leger.(2) According to this chronology, the modern painting has been accepted and cultivated for the last hundred years, and its centenary heritage has endowed it with a prestigious historical legitimacy. Although repeatedly proclaimed dead, unnecessary, obsolete or powerless, it has survived thanks to its infinite openness and capacity to absorb and assimilate all transformations, subversions and criticisms inscribed in its formal and semantic frames.

Dilemmas about the essence of image, as well as those about the nature of painting and its position at the actual moment are points of departure for Zolt Kovac’s artistic deliberations. Since his early experiments in TheGood and the Bad Painting (2000), where he charges the stability of the system of evaluation of artist’s formal success; since his subversive and witty statement on the necessity to demystify the institution of art and the figure of artist in Painting Develops Supernatural Abilities and Esthetic Experience Develops Supernatural Abilities (2000), Kovac raises intriguing questions about the status of painting at the introspective level, within his own artistic position, as well as the power of painting in the larger field of its interaction with society or observer.(3)

Kovac’s continues his exploration of the painting’s capacity to bridge the gap between art and life in Invisible paintings (2003), Empty time (2007-2008) and Paintings of Superfluous Information, ceaselessly affirming the need to free the medium from the constraints imposed to it by its pedigree of an exclusive historical position, by the imperative of complex theoretical-aesthetical elaboration, by autoreferentiality and complacency of painterly medium and authors themselves. Stupid paintings (2008-2009) have also been created on this persistent path of positive banalization. They reintroduce abstraction into Kovac’s artistic repertoire as a field for maneuvers of subversion and play with the encumbering legacy of modernist painting. As he studied at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Belgrade within unmistakably modernist approach to arts and artistic creation, his response to the legacy of this significant artistic narrative results from his situation: aware of unfeasibility and obsoleteness of exclusive and unidirectional artistic efforts in the contemporary circumstances, he relativizes and subverts the ponderous, powerful substance of painting in his wish to participate in the transformation of the relationship between a painting and its social context. For Kovac, a painting is not an exclusive, almost inaccessible object of esthetic or intellectual enjoyment, but rather a visual message tending to lure the observer into an exchange of life’s experiences and everyday situations.

Brilliant Paintings, just like The Good and the Bad Painting or Stupid Paintings, choose abstraction as their formal language. Adopted consciously, abstraction is not the final objective of the painter’s exploration. Nor is it a statement on his spiritual or aesthetic expression. It is reduced to a means for a series of farther interventions at the level of meaning, position and reception of the painting medium. The first intervention appears in the title of the series: the word brilliant does not imply that these paintings have superior quality or artistic value, but rather refers to the technical side of their creation – the application of metallic car paint onto aluminum, resulting in the high shine of painted surfaces. The next intervention takes place in the field of autonomy of (abstract) painting. The artist introduces textual messages into an abstract composition, thus transcending imposed linguistic codes of comprehension and definition. Its reception by an ordinary observer is made much easier by messages – Thank you, Please, All right, I want, Yes!, I love, Together, I am listening, Order is threatening, Inherited ignorance of communication, Benign evil, Indifferent to truth, Declarative State, The state will not solve our problems, Islands of the interested – figuring as the third intervention at the level of reception. Through this intervention Kovac simultaneously controls and confuses the relationship between painting, observer, and meaning created in the interaction of a painting and its observer.

Having in mind traditionally high and popular status of painting in the local milieu (compared to other artistic disciplines and practices), and pursuing its long-lasting project aimed at creating life for the contemporary painting in the sphere of everyday life through demystification and banalization, Zolt Kovac, in his most directly engaged project by now, “compromises” paintings by texts to make them resound “more loudly” through the observer’s space. The messages these paintings carry – the words shining from their surfaces – are concepts recognized by the artist as signifiers of the crisis of collective mentality and failures of the state’s functioning (in large paintings) or as expressions which are missing or rather disappearing in everyday communication (in small paintings).(4) In his utopian belief that a painting has the power to incite change of consciousness, understanding and thought in its social surrounding, Kovac in his Brilliant Paintings (as in his other works) does not undermine the painting medium’s authority with the aim of destructing it, but rather with the view of adapting its transforming capacity to contemporary circumstances. Although at first sight they might seem didactic, Brilliant Paintings function as open communication fields that do not impose a dogma, but rather launch a dialogue between art and life – the mission Zolt Kovac has been actively on for years.

(1) In 1913 were created Marcel Duchamp’s first readymade, Umberto Boccioni’s sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Pablo Picasso’s Guitar, rough draft for Kazimir Malevich’s futurist stage for the opera Victory over the Sun (where his first Black Square appeared), apstract paintings by Franz Mark, Ferdinand Leger, Piet Mondrian, Robert Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky’s illustrated book Sounds etc. At the very important International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as Armory Show, organized in New York, works by many European artist were displayed (Cezanne, Degas, Renoir, Monet, Seurat, Van Gogh, Brankusi, Matisse, Manet, Signac, Braque, Gauguin, Duchamp and others).

(2) See more in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buhcloch i David Joselit, Art since 1900. Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, (2nd edition), Thames & Hundson, London 2010, p. 118-124.

(3) Compare Siniša Mitrović, Boris Mladenović, “Umetnost ponekad predstavlja pravo osveženje…”, Umetnost je ponekad pravo osveženje, Dom omladine Beograda, Belgrade 2001.

(4) From an interview with the artist (May 2, 2013).

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

No Comments